What do Twitter, Zoom, Facebook, and Microsoft (among many others) have in common? Unfortunately, it’s that they’ve all had a security breach of some kind in the past couple of years – the vast majority of which due to some level of social engineering. Social engineering remains one of the most common ways that attackers (“black hats” as we call them) gain access to and exfiltrate data from organizations. It is not uncommon for that to be the first vector, which is then, of course, followed up by more technically advanced methods of hacking into various systems within our organizations. So first off, what is social engineering?

At its core, social engineering is the act of using some level of deception to manipulate an individual or several individuals into divulging confidential/personal information.

Ultimately, the goal of social engineering is to gain access to more sensitive information within organizations to get at financial or corporate data. If it’s a government target, the goal can be to get at confidential – even secret – documents and data that can then be used for political purposes.

Organizations that have suffered a social engineering attack in the last two years

Quite a few logos up there, huh?

Types of Social Engineering Attacks

Regardless of the specific goal, the most basic types of social engineering attacks are phishing, pretexting, baiting, quid pro quo, and tailgating. Let’s expand on each of these a bit.

Phishing

Phishing is a way of sending communications in a spoofed or deceptive manner in order to gain access to someone’s information, be it to get them to download a piece of malware, or perhaps voluntarily divulge some level of information in order to steal money or even identities. It’s a huge problem, and we are all very susceptible to it.

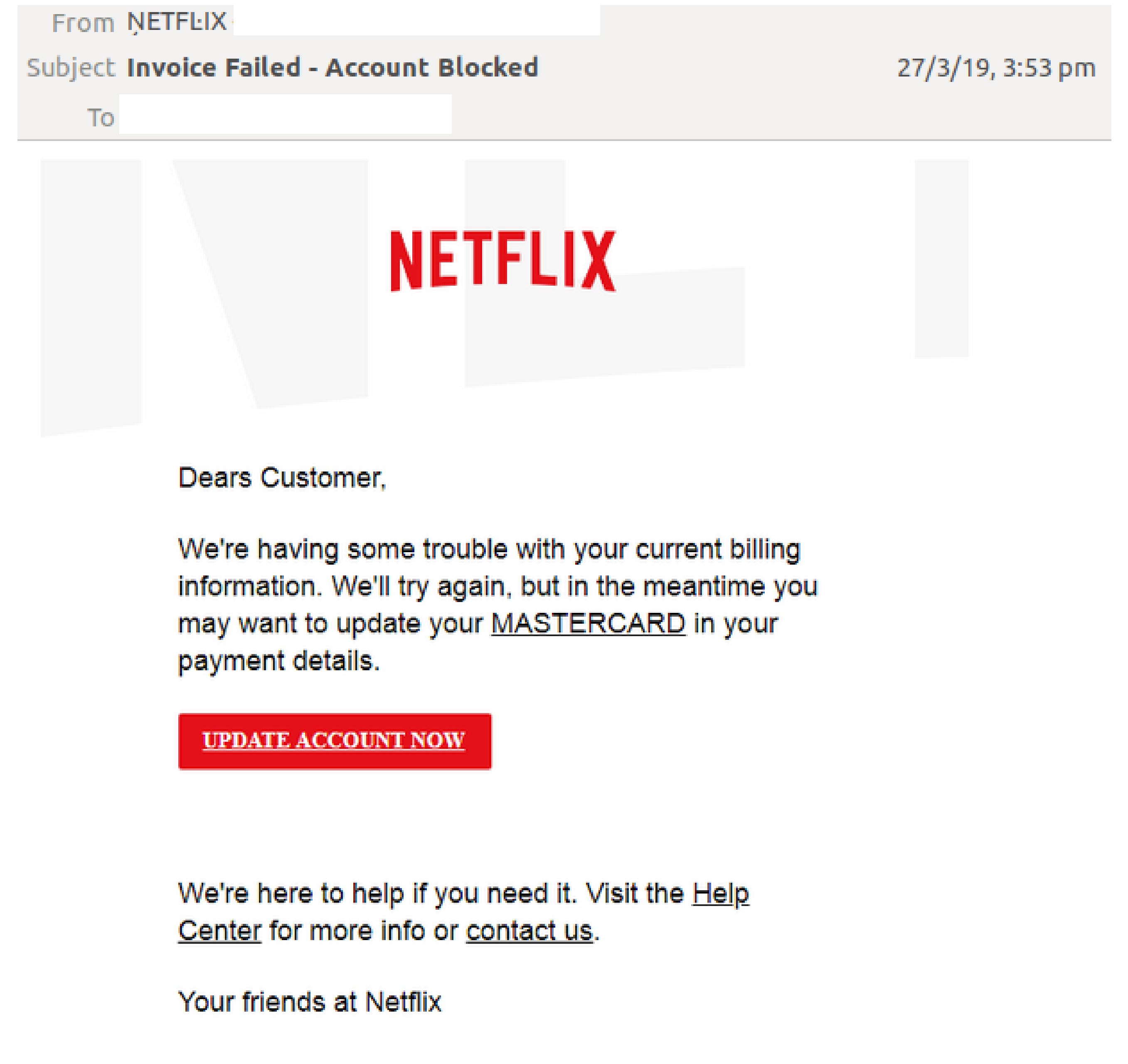

Example of phishing

Spear phishing is a special type of phishing where attackers hyper-target a specific group or a specific node. While phishing is generally distributed widely, spear phishing is localized.

Example of spearphishing

Pretexting

Example of pretexting

Pretexting is the approach of coming in with the sense that something is urgent and needs to get done immediately. This often takes shape as an authoritative request or demand from the spoofed or hacked email address of someone in upper management or leadership. It’s meant to evoke some level of threat or fear to get you to act without thinking clearly.

Baiting

Example of baiting attack

Baiting is much like actual fishing (we use some interesting terms in the InfoSec world) in that it involves some sort of promise. This can be a beneficial promise, or it can be a promise that something bad will happen if you don’t follow the given instructions. Baiting is a very common way that, especially individuals, get socially engineered. For example, “If you click on this, your friend, the Nigerian prince, will send your millions of dollars.” That’s a pretty common baiting scheme.

Quid Pro Quo

Example of quid pro quo social engineering attack. Login credentials and file download in exchange for continued use of service.

This is something in exchange for something else. “If you provide me with X information, you will get something in return.” This is similar to baiting, but with more emphasis on the transactional nature of the interaction.

Tailgating

While the tactics above are usually electronic or voice-based, tailgating is much more physical – and it’s pervasive enough to warrant an entire security industry based around physical penetration testing. The idea is that I show up and look like I belong; I look like a delivery person, or a maintenance person, or maybe I look like a nice vendor who should be coming into the building with you. I either walk in directly behind you, mooching off of your legitimate access, or frequently, I’ll come up to a doorway and pretend to be a professional. Maybe I have my hands full with boxes because, hey, I’m a delivery person from FedEx. As I’m struggling with the boxes, I say, “Can you let me in so I don’t have to put all these boxes down?” And lo and behold, most of us, wanting to be helpful people, will respond with, “Oh yeah, your arms are full, that’s probably a pain. Let me help you get in.” It’s a common physical social engineering technique that a lot of attackers use.

How effective is social engineering?

Very. According to APWG, 88% of organizations around the world experienced some level of spear phishing attempt in 2019. That means spear phishing is happening all the time.

This second statistic is maybe the more terrifying one: Per proofpoint, 65% of U.S. organizations experienced some level of successful phishing attack in 2019. Sixty-five percent. That is a staggering number when you think about it. It sends chills down the spines of, not just me as a security person, but most of my leadership as well. The idea that well over half of all organizations are successfully phished in some fashion means some level of data is exposed. It should give all of us some pause.

Social engineering is expensive. More alarming numbers ahead:

- Over $17,000 is lost every minute of every day to successful attacks. That’s a substantial sum of money. So, you can see why people would continue to utilize this particular attack vector to get access to things. It’s a very profitable way of breaking the law.

- Data breaches cost enterprises an average of $3.92 million per organization. For some organizations, that’s an annual budget. So, thinking of that as an average is pretty scary as well.

- The average BEC wire transfer attempt (BEC being a compromised or spoofed email, for example, your CEO suddenly sends over an urgent message for you to wire transfer money to XYZ corporation) was for an average of $54,000 in the first quarter of this year. Harkening back to the fact that 65% of organizations experience some level of successful phishing attack, that’s a lot of money being transferred.

The irony is that phishing is generally not all that sophisticated. So why is it effective, you ask? Well, the effectiveness of social engineering, and phishing in particular, leverages three primary motivations: greed, fear, and urgency.

Keys to Social Engineering: Greed, Fear, and Urgency

If I receive an email in my business email account that’s promising me millions of dollars, I’m probably going to look at that pretty skeptically. In that case, the greed factor is probably relatively low for business users. Outside of work, however, if you receive something in your personal email account that shows some kind of benefit from clicking on a link or downloading an attachment (an iTunes gift card perhaps), then chances are you’re going to be more susceptible. Greed is something that does drive us personally.

Urgency, from a professional standpoint, is the more effective motive. The idea here is for attackers to say, “This must be done so quickly that you don’t have time to really review it or ask any questions,” because once you start asking questions, of course, the scheme breaks down, and the chances of it actually working are reduced significantly.

Fear is a motive that is quite effective in both personal and professional settings – the idea being that if you don’t do something, something bad will happen. If I receive a message from my boss that says, “You must do this right now or else… ” chances are I’m going to do that thing because I want to avoid any negative consequences that could arise from not handling whatever is being asked of me.

Personally, these fear tactics frequently come through voice – “vishing” (voice phishing, as it’s called). Most of us, at one point or another in the past few years, have gotten some sort of phone call where they tell you that the IRS is coming for you and they’re going to take all of your assets because you owe them thousands of dollars and you need to call this number right away and provide them with all your personal information. These are amazingly effective.

Volume of Social Engineering Attacks

While the three factors listed above are certainly big ones, social engineering attacks also rely on a fourth key factor: volume. The phishing emails you receive probably went to hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of other people. Attackers don’t need everyone to click on their malicious links; they just need a few people to take the bait. If the average attack is costing close to $20,000, and one guy is sitting in his basement buying email lists, how many people does he really need to click on that link to make a pretty decent profit margin? At twenty grand a pop, it’ll only take him ten victims to land $200K.

Speaking of volume, there is one less common phishing technique that doesn’t get used quite as often because it’s a little harder to be successful with – and the pool is much smaller. It’s a technique called whaling. Whaling is a phishing technique where attackers target people of substantial financial means. If the attempt was on a company, for example, the target would be senior level executive management; it would come for them directly or as an attempt to gain enough of a foothold that they could be impersonated to close out bank accounts or talk to the CFO and demand money.

Again, whaling is not as common because the reality is that it’s simply a much smaller pool to begin with – and because phishing tends to be such a volume game, whaling is not quite as successful. When it is successful though, the idea is that they’re landing a whale. If you get one person at that seniority level, then you have likely given yourself a huge pay day.

Social Engineering Attacks: Impersonating an Authority Figure

We’ve talked about how most social engineering involves someone masquerading as someone else. The most effective way to do that is to masquerade as a boss. At Beyond20, we get this sort of email at least once a month, and it usually goes to somebody new. It comes from our CEO saying, “Hey, I’m in a meeting right now. But can you please send me XYZ information via text? Here’s the number to send it to.” Now, it’s obviously not from our actual CEO, but it’s usually the people who are relatively new to the company who freak out a bit when they receive it.

It’s not a particularly sophisticated attack. It’s super simple, all text. But again, you can see how enticing it would be, especially for a new employee who’s hoping to impress the boss and show everybody they’re a big team player who will pull their weight. The interesting thing is that this sort of attack is exacerbated these days because most of us are working from home. We are not sitting in an office 10 feet away from that person where we can just go, “Did you just send me this email?” This means I don’t really know exactly what my CEO is doing or where she might be in this very moment. She very well may be in a meeting, so I have to maintain vigilance when I see something like that and reach out to her and say, “Hey, did you just send me an email?” And if she responds, “Yes, I need you to do that.” Well, then I know she’s probably legitimate. But if she says, “No, I have no idea what you’re talking about.” Then I can know better than to respond to it.

How to protect our employees from social engineering attacks

There are plenty of technical measures we can put in place to protect our employees (spam filters, phishing filters, what-have-you) and you should definitely be looking into those if you don’t already have them in place – but they don’t stop all of it. Many attackers are very sophisticated in their understanding how these programs work because they have access to them, too. They can figure out the ways around, they can find the loopholes, they can discover the ways to get through. So technology is a big part of it, but it’s not everything. There are three basic tenets that I have around how we get our employees to become less of an inadvertent security threat.

Security Awareness Training

Train, train, train. Never stop training. Studies by KnowBe4, an organization that specializes in awareness training, have shown (though they may be slightly biased) that organizations that stop their awareness training, or even pause it for some period of time, almost immediately start to see a slip in successful detection of attacks. People become complacent; they stop paying attention to the banners that tell them an email is coming from an outside source, etc. So train often, train early, make sure you have some sort of onboarding training for security awareness. Make sure everyone understands the policies in place and how to spot social engineering attacks.

Then run social engineering exercises.

Send some phishing emails to your own organization. Leave that USB key sitting out on a conference table for a few days to see who picks it up and plugs it into their computer. We want to conduct dry runs for the things that attackers will certainly use to get access – we want to get people aware and keep them somewhat on their toes. The goal is to make sure they’re aware that this stuff is always happening, but in a controlled environment. If I send a phishing email and you click on the link, well, there’s not any damage that’s actually done, but it lets me know, “Oh, I should probably sit down with that person and say, “Hey, you clicked on the link in this email. Why?” Understanding why they did it is a good way for us to better train going forward and perhaps even tune some of our technical controls to keep it from happening going forward.

Note: Never do this as a way to punish. That’s the exact opposite of the way to get people on board and excited about detecting attacks and reporting on them. This is a learning exercise – no shaming allowed.

Transparency

This is where security teams tend to fall down. We like to keep things close to the vest because security is all about being, well, secure. But I’m here to tell you, if you don’t tell employees when an attack has occurred, they’re never going to know and as a result may never take the threat seriously. If you don’t think it’s actually happening, you are less likely to be concerned about it ever happening. So if an attack is reported, make sure everybody is aware. “Hey, guess what? We were attacked.” Even if it was an unsuccessful attempt, say, “Hey, you know what? This happened and I want to give kudos to everybody who helped to stop it.” Or “We were successfully attacked. And here is what we’re doing to make sure that that never happens again.”

Collaboration

Make sure security is involved at all levels, not just with respect to technology. Physical security: understanding the privacy of our own employees and respecting that. Phone security: When someone calls asking for information, how do we react to that? What’s our policy? Security needs to be involved at all levels.

And join the fight. You should be involved in this. It’s one of those great slogans you see in airports and we see it here in DC on the metro: “If you see something, say something.” If you see something suspicious, report it. Talk to somebody, even if it’s not a security person. Get with a manager, let them know. If you are in management, talk to your security officer. Ultimately, security is everyone’s responsibility.

How can we help on an individual level?

Password safety still matters. We need to make sure that our passwords are secure and that we’re not sharing passwords with people. What does a secure password look like? It’s one that’s hard to guess! Historically, we thought lots of different character types, numbers, capital letters, lower case letters, and special symbols in a really long and hard to read password was the way to go, but that actually leads to more compromise because people then end up writing them down somewhere, etc. Newer thinking on this is that you should be using common phrases, a sentence, as your password. Sentences are very difficult for brute force engines and password dictionaries to decipher because they are not natural language processors. What they’re trying to do is pattern match. A brute force password attacker is going to hammer through every possible combination of characters. Conversely, to get to the combination of characters that makes up “the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog”, is going to take it a very, very, very long time. Nonsensical phrases are even better. For a comprehensive look into the fallacy of security with complex passwords, check out this article.

Additionally, treat your computer like it contains valuable company information. ‘Cause guess what? It does. We’re all working from home now, which means we probably brought a laptop that was issued to us by our company home with us. If we need to get into the network, there’s probably some kind of VPN or other secure way to do that, but it’s usually attached in some way to the computer we have. I recommend that any time you are on any network that is not a protected office network, you should be using a VPN. Your home private network probably is okay. But I would say, certainly being someone who traveled a lot before this year, using a VPN when I’m in any sort of hotel or the airport or anywhere where there’s public access available to a network, definitely be using a VPN (preferably one with quality offshore proxies and does not log information).

Further, if I leave my computer unlocked or if I leave it sitting out at a coffee shop or something like that, and somebody picks it up and takes it with them, I have just compromised massive amounts of highly sensitive data, probably, about my company. So treat your computer like it’s important because it really, truly is.

Finally, be careful with your personal information because it can, and will, be used against you at some point in a social engineering attack. That means what you share on Facebook, what you share on Twitter, what you share on Instagram, putting all your kids’ birthdays out on Facebook and then using your kids’ birthdays as your passwords – it doesn’t take long for an attacker to figure out that correlation. So be very careful with what information you share publicly. We talk about privacy not really existing in the United States anymore, and that is largely true in my opinion. So be very careful with what you divulge, because if you don’t, chances are that’s going to be used in some kind of attack on you in the future.

Those are three big things, I think, around personal responsibility: password selection, computer safety, and personal privacy.

Let’s talk some more about security training.

I call Security+ the mile-wide and inch-deep class on security. It does cover a lot of the technical controls and technical aspects of security, but it also definitely covers things like social engineering, so phishing and vishing and tailgating, all of that sort of thing. It is a more technically challenging course, so if you don’t have a background in IT and have no background at all in security, it might be a little bit on the high end for you. However, we do offer a security fundamentals course which does cover a lot of basic administrative controls and just some basic familiarity with a lot of the terminology within information security. So, knowing what phishing is, knowing some of the protocols that go into it, understanding those things, that is a great primer for those folks who are not necessarily IT people but do want to have a little bit more information. Also, a proper security awareness program within your organization, if you don’t have one internally. And it’s something that we certainly recommend gets developed, so that you do have a way of training folks as they come on board. We can help to design one of those alongside you, so if that’s something you’re interested in, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

When I’m teaching introductory security classes like Security+, one of the things I often say is, if for absolutely no other reason – if I didn’t have any other reason to think that security was important, (and I have plenty of reasons to think security is important, but if I didn’t), consider this: If my company had a severe, serious security breach and loss of data and our reputation were irreparably damaged, I may not have a job. And I like having a job. So, at its very core, self-preservation is a valid reason for security. But we also want our companies to be successful, we want to be secure, we don’t want to lose our data, and we don’t want to lose money. We want things to go well, and there are plenty of people out there that would take it from us if we don’t remain vigilant.