The Need for the “Dictionary of Digital Business”

Welcome to the World’s first Dictionary of Digital Business! While the concept of digital transformation is not particularly new (people have been using the terms since at least the 1990s and in various forms much earlier than that), the phrase itself is surprisingly elusive and ill-defined. So too are many of the terms and concepts associated with digital business. Even when definitions exist, they are rarely standardized, agreed upon, or collected in the same place. While the ubiquity of the Internet and open collaboration model of Wikipedia seem to make structured dictionaries and encyclopedias obsolete (read below how Encyclopaedia Britannica has gone digital), organized and vetted knowledge still has a role to play in supporting communities of practice and in creating shared language.

This article is the preamble to the World’s First Dictionary of Digital Business and provides its justification, background, description of content, organization, and planned evolution. Last, this article will share a brief history of the rise and fall of structured and unstructured knowledge, forming the foundation for how we understand and use words today and the inspiration for this dictionary.

The Case Against Traditional Dictionaries and Structured Knowledge

Dictionaries, encyclopedias, and reference publications of all persuasions have gone the way of Latin, the sentence diagram, and house calls from personal physicians. Although you won’t quite find them entombed with the bones of the tyrannosaurus, the dusty shelf and yellowed pages are testament to their disuse. It’s not that knowledge has stopped expanding or that people have become disinterested (or for the etymologist, is it uninterested?) in learning. In fact, given its broad and distributed nature, knowledge management, collaboration, and knowledge sharing is more necessary than ever. In digital business, the proliferation of technology has driven the need for the rapid acquisition of new skills and the adoption of continuous learning approaches. Indeed, knowledge is as alive as ever! Instead, a silent gradual rebellion has occurred against structured knowledge.

Why the Dictionary of Digital Business, you ask? A dictionary provides information on expressions – typically words – of a language, while an encyclopedia tells one what is known about an object, or objects of a certain kind.

Doing away with paper

The dictionary and its lexicographical (alphabetically ordered) cousins are the very definitions of structured knowledge and are also obvious candidates for digitization. After all, the printed versions of these tomes are heavy, cumbersome, use a lot of paper, and are expensive. But why not do away with paper entirely? Print versions cannot be updated frequently and require a significant amount of effort on each occasion. Their digital relatives can be updated continuously and easily, are much larger in size, are more portable, and are easier to search. Moreover, connecting one topic to another can be more readily achieved through the use of hyperlinks. Consider this, the print version of the Encylopaedia Britannica, published in 2002, included 65,000 articles, 44 million words and was sold to consumers for $1,395. By comparison, Wikipedia has more than 4 million articles and 2 billion words and is free to consumers (though, as a nonprofit, Wikipedia asks for donations). In 2010, due to competition from the internet and, specifically, Wikipedia, Encylopaedia Britannica announced that, after 244 years, they would be printing their very last edition. More on this story later.

Paper is not the real foe

However, paper is not the fundamental argument against the dictionary family. Dictionaries and encyclopedias can be (and have been) published online. Rather, a war is being waged against the notion that documented knowledge should be vetted by so-called subject matter experts, peer-reviewed, or organized around domain bias. While it is difficult to pinpoint the origins of this disestablishmentarian cultural zeitgeist (please excuse the redundancy), there is no doubt of its existence. Although the practical reasons of speed and convenience dominate, there is also a notion that there is a disconnect between the “experts” and the practitioners. Indeed, everybody is an “expert” in their own minds. Isn’t there a certain wisdom in the crowd of the self-anointed? And if the whole point of language and knowledge is to improve communications and share, why rely on recognized subject matter experts? Why not let the crowd define language and knowledge for themselves, for the needs of today? Devil-may-care!

Words Matter (and Move) when it comes to Digital Business

Words matter. While the word police won’t penalize you for calling a major Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) implementation a “digital transformation,” conflating automation with digitalization is likely to confuse employees and lead to a misunderstanding of anticipated results for a digital initiative. When an executive returns from a conference and says “we all need to get on board with digital transformation” does she mean she wants to use a vendor’s cloud technology or purchase artificial-intelligence tools? Or is she talking about using technology to fundamentally change the way the organization operates? The fact is there exists no single definition of digital transformation and no single source where words associated with it are defined. The closest one can reliably come to a single source of “truth” on Digital Transformation (sometimes referred to as DX or DT) is the Digital Practitioner Body of Knowledge (DPBoK), published in 2019. And even in that ambitious and much-needed publication only seven words are actually defined in the Terminology section.

Words create an atmosphere

All words have a certain atmosphere. For many common words, a commonplace definition suffices for general comprehension. A mariner could better explain the difference between a boat and a vessel and a ship, but we all get the point that water is involved, and life vests are a good idea. More than the definition, context helps a lot. When a word is used often enough and with enough consequence it undergoes a transformation into a topic or domain, and in addition to atmosphere it acquires a certain gravity. At this point, a free-for-all approach to word usage goes beyond inappropriate; it actually gets in the way. Standardization is the solution.

Terminology Confusion Online

A germane and useful example can be found in the words digitize and digitalize. Both Merriam-Webster and Cambridge Dictionaries define digitize as something along the lines of:

To convert data (photographs, sound, printed text) into a form that can be processed by computers. To start to use digital technology.

In both cases, they list digitalize as a synonym and use an identical definition. Similarly, DPBoK defines digitize thus:

The conversion of analog information into digital form.

However, DPBoK defines digitalize in a different way:

The application of digital technology to create additional business value within the primary value chain of enterprises.

As discussed in “How IT Can Enable Digital Strategy,” to some Digital Transformation means nothing more than turning physical media into an electronic format – scanning paper documents to create soft copies, storing sound and image files electronically and the like. For others, it means using cloud technologies to store data and applications in a virtual format, often offsite and hosted by a third-party vendor. In this sense, digital transformation is like beauty, in the eye of the beholder.

A more holistic definition of digital transformation – and the one supported by this dictionary –

Is when technology is applied to fundamentally change the way organizations interact with customers and how work is accomplished within the company itself.

The Case for Curating Terminology

The rise of the digital business and need for curated, standardized verbiage to ensure common language and understanding was the impetus for the creation of the “Dictionary of Digital Business”. The following sections will provide an overview of the sources that were used in creating the dictionary, details around the scope of what’s included, how it’s organized, and plans for future expansions and continuous improvement.

Sources for the “Dictionary of Digital Business”

Definitions in the Dictionary of Digital Business are drawn from a variety of sources including: Axelos (ITIL, PRINCE2, AgileSHIFT), The Project Management Institute (PMI’s PMBoK Guide), the Digital Practitioner Body of Knowledge (DPBoK), the Agile Alliance, Barron’s Dictionary of Business Terms, Wikipedia, various online digital marketing dictionaries, Internet sources, and several subject matter experts. In selecting definitions, there was a strong preference for using authoritative sources and commonly-agreed upon meanings. In some cases, definitions are abbreviated, explained in more detail, or paraphrased (hopefully without losing the original meaning). In cases where there was no consistent or commonly agreed-upon definition or when no definition at all exists, I crafted the best definition I could muster. Indeed, I may have even coined a few words.

What is & isn’t Included in the “Dictionary of Digital Business”

The primary goal of the Dictionary of Digital Business is to craft a common language around Digital Business and Digital Transformation. Given the broad and evolutionary nature of these topics, narrowing the scope is no small feat. It means saying “no” to words more often than saying “yes.”

The Dictionary includes terms related to Digital Strategy and positioning, Practices, Frameworks, Risk, Tools, Technology, Continual Improvement, Innovation, Service Management, Software Development, Agile, Project Management Approaches, Consumer Experience, and Digital Marketing.

The Dictionary does not include every word associated with a subdomain (what I call a Knowledge Salon). For example, although many Agile definitions are included, only those most pertinent to Digital Business appear. The reader interested in Agile has other more comprehensive sources for Agile terminology.

Organization of the “Dictionary of Digital Business”

In the fifteenth edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1974 (more on its history below), a Propaedia was introduced as a companion publication to the alphabetically organized volumes of the encyclopedia. This ambitious publication was intended to serve as a reader’s guide and provided a topical outline and hierarchical organization of the volumes. More than this, the goal was to provide a logical mapping or framework of all human knowledge and to suggest a roadmap for how a learner could study in-depth each major discipline.

Likewise, this Dictionary of Digital Business is organized in multiple ways:

- Alphabetical

- Five Pillars of Digital Business

- Knowledge Salons

- Neural Value Streams

The first, alphabetical, is obvious and obligatory and requires no further explanation.

The Five Pillars of Digital Business are the main courses of knowledge that support the study of digital business. They are:

- Digital Strategy and Positioning

- Practice and Frameworks

- Risk

- Tools and Technology

- Continual Improvement and Innovation

Another lexiconographer might well have organized the top tier along three pillars or seven pillars or any other number and have chosen different topics. To each his own. The “thing” itself has no native organization. Describing and organizing the phenomenon is inherently artificial and is meant as a guide; not an absolute or rigid path. Indeed, in subsequent releases, it is entirely possible that the five pillars change.

Knowledge Salons are the second level of the hierarchy. They can be thought of as subdivisions of the five pillars. It is anticipated that these will change frequently as new areas of study are created or recede into obscurity. Knowledge Salons include important domains such as Data Management and Analytics, Project Management, Software Development, and Agile, just to name a few. Any one of the salons could be its own pillar in a different publication. Indeed, many books have been written on each of these topics.

Neural Value Streams represent the most complex and fluid aspect of the structure. They combine the concepts of neural networks (artificial pattern recognition maps loosely modeled after the human brain) and value streams (a series of steps and activities to create value). Neural Value Streams relate Knowledge Salons to each other in ways the practitioner may find useful. For example, Software Development (part of the Tools and Technology Pillar) is linked in a neural value stream to Agile (part of the Practices Pillar), which in turn is linked to Project Management (also part of the Practices Pillar). The dictionary includes neural value streams that make sense to the editor, but readers are encouraged to create their own paths or learning.

Visual Map

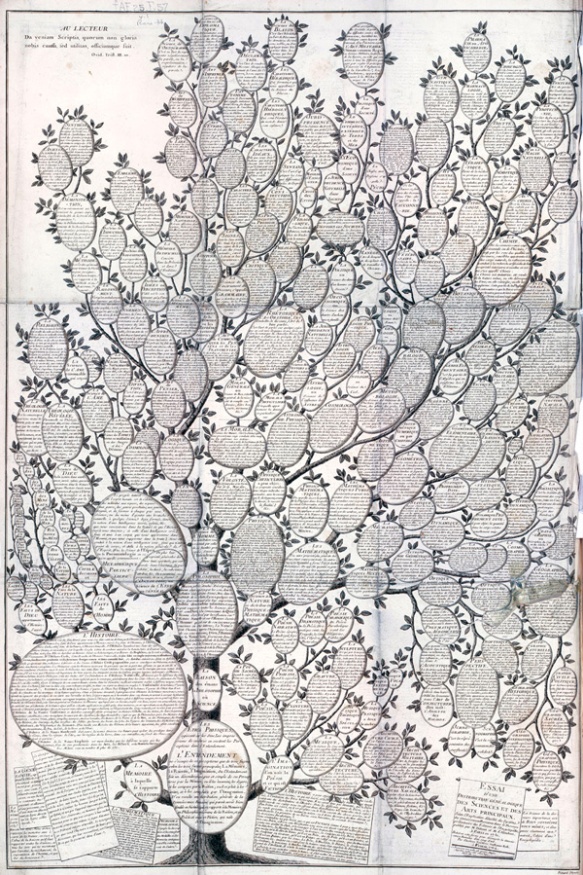

Paying homage to Francis Bacon, Denis Diderot (see more details on these gentlemen below), and the back of many children’s cereal boxes, the Dictionary of Digital Business includes a visual map to depict how knowledge is related. Currently, the visual map is organized by pillar and knowledge salons are related to their “parent” pillar. Some of the main neural value streams between and amongst salons are mapped. However, the inaugural version of this map is admittedly simple and does not show every relationship. In the spirit of open learning, the practitioner is encouraged to create their own maps to the extent that it increases the value or depth of their knowledge. The current visual map may be further developed in future releases.

The Interesting and Important Work of Others that Inspired this Dictionary

To better understand where we’ve come from as well as where we’re going with words and how they move and shift, it’s helpful to look back at the rise, decline, and transformation of the encyclopedia along with the rise of free and open knowledge.

The Encyclopedia as the Ultimate Rebellion – The Story of Denis Diderot

I would argue that the Encyclopedia, not crowdsourced expertise, is the ultimate rebellion against authority and knowledge hoarding. At least, this is what the famous French Encyclopedist, Denis Diderot, thought when he said he wanted to “change the common way of thinking.” Begun in 1749, the Encyclopédie, or Reasoned Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, and Trades was initially intended as a French translation of Ephraim Chambers’ 1728 Cyclopedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. Instead, through Diderot’s collaboration with Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert, the Encyclopédie not only influenced the era of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution but, over time, also democratized knowledge. Prior to Encyclopédie, most knowledge was reserved to the monarch, the upper nobility, and religious orders. Encyclopédie took advantage of rising literacy rates in France to disseminate vetted knowledge to the burgeoning bourgeoisie.

Three characteristics of Encyclopédie contributed to its success. The knowledge contained within it was curated, structured, and intentionally biased. Although Diderot wanted to undermine the elites’ stranglehold on knowledge, he was wise enough to understand that unvetted knowledge was often inaccurate, narrow in its scope, and prone to superstition and commonsense judgement, which is often anything but.

Diderot organized Encyclopédie around three main branches: Memory, Reason, and Imagination. Each of these branches was further structured and decomposed. For example, Memory, or what we commonly call History, is broken down into Civil, Ancient, Modern and Natural. Reason is decomposed into Philosophy (Science of Man, Science of God, Science of Nature). Imagination is composed of Poetry, both Sacred and Profane. A fan of the renowned Francis Bacon who created a famous knowledge tree, Diderot categorized knowledge into a “Figurative System of Human Knowledge” and created a visual map as shown here to accompany articles in Encyclopédie.

The knowledge contained in the volumes was intentionally selected and the contributing authors carefully chosen based on their intellectual prowess and areas of specialization. Encyclopédie, ultimately containing 28 volumes, 71,818 articles and 3,129 illustrations, was intentionally a biased publication. Although “bias” has taken on negative connotations over the years, in this context it had the positive effect of directing the focus of knowledge, excluding unvetted hearsay and superstition, and promoting the scientific progress associated with the Enlightenment movement.

But extreme vetting has its downfalls. In fact, Diderot famously said the Encyclopédie project ruined his life. Indeed, it took twenty years to produce the single edition of Encyclopédie, and even in a time when knowledge seemed to be discovered more slowly, updating the volumes was tortuous. Thankfully, knowledge doesn’t work that way today.

The Transition from Print Dollars to Digital Pennies – Encyclopeaedia Britannica

Similar in its goals of organized and scrutinized knowledge, another reference work, the venerable Encyclopaedia Britannica, founded by Colin MacFarquhar and Andrew Bell, got its start in Edinburgh, Scotland a few years later in 1768. This first English language encyclopedia was much smaller and less general than Diderot’s Encyclopedie. Encyclopaedia Britannica’s innovation went beyond linking one subject to another; in addition to that they recruited experts to introduce major topics with an article or “treatise” that placed the topic in a specific context. Treatises ranged in length from a few paragraphs to over 150 pages. The initial publication included forty such treatises. Thus, readers interested in quickly finding a definition could do so; and those with an appetite for in-depth knowledge could read an article from a subject matter expert.

Initially, Encyclopaedia Britannica was sold from the publisher’s offices in Edinburgh, but in 1920 it was purchased by Sears Roebuck and Co. and its headquarters was moved to Chicago. To this day, many still consider it the most comprehensive and authoritative encyclopedia in history. More than that, it is an example of one of the most successful direct marketing campaigns. Encyclopaedia Britannica targeted middle class families and played to their aspirations of giving better opportunities to their children through learning. (Indeed, as a child, I had a set of the World Book encyclopedia, a knock-off of Encyclopaedia Britannica; World Book was created when it was observed that Encyclopaedia Britannica was not appealing to younger readers.). Over the years, Encyclopaedia Britannica successfully sold leather-bound books until it reached its peak sales in 1990 with $650,000,000 and 100,000 volumes. Then came the CD-ROM.

Almost overnight, the CD-ROM (Remember those?) disrupted the world of printed content. Microsoft licensed content from a smaller and greatly inferior encyclopedia, Funk & Wagnalls, and branded their CD encyclopedia as Encarta. Encarta sold for between $50 and $70 but was often given away for free as a promotion for PC sales. Although it was no match for Encyclopaedia Britannica in terms of quality, it soundly beat it on price. Encyclopaedia Britannica’s print publication sold for $1,500 to $2,200. Encyclopaedia Britannica struggled to create its own CD version because its content was so voluminous that it would not fit on the new media. Eventually, to remedy this limitation, they released a CD without any images. They gave it away for free to purchasers of their print publication, but anybody who wanted to purchase the CD as a stand-alone version would have to pay $1,000. Too little, too late, by 1994 Encyclopaedia Britannica sold just 3,000 units of its print volumes and was put up for sale in 1995.

In 1996, Encyclopaedia Britannica was purchased for $135,000,000. Their digital transformation was gradual. Over time, they shifted their focus from selling print encyclopedias to households to creating educational materials for schools.

By 2003, they returned to profitability, mostly due to their educational sales. 2010 was the last year that Encyclopaedia Britannica printed a paper version of its encyclopedia. By this time, 85% of their revenue was coming from schools who were purchasing subscriptions to their educational materials. According to Michael Ross, Senior Vice President of Encyclopaedia Britannica, they shifted from “Exchanging print dollars for digital pennies.” In other words, when they were in the business of selling print volumes, they could only reach a limited number of customers. Although the price per encyclopedia set was high, not many customers would purchase it. By contrast, they currently sell subscriptions to their educational materials to schools for about $0.75 per student per year but reach an estimated 100 million consumers. Although Encyclopaedia Britannica is now a private company and does not disclose financial information, it is estimated that between 2012 and 2019 their profits have grown by 15% per year.

So, how does Encyclopaedia Britannica compete with the free and “good enough” information on the Internet?

The Rise of Free and Open Knowledge – Wikipedia

Launched in 2001 as a nonprofit organization, Wikipedia’s approach to creating knowledge is fundamentally different than the tactic your father’s Encyclopaedia Britannica took. Wikipedia’s core tenant from day one is that “There would be no central authority controlling content.” Instead, self-proclaimed experts, enthusiasts, and communities of practice create and refine articles or “wikis” themselves with few rules of engagement. This crowdsourced open model of knowledge generation is certainly popular. Consider this: Wikipedia is the fifth most popular website in terms of overall traffic, has a monthly readership of 495 million, and has 15.5 billion page views!” Indeed, some of the concepts in this Prologue were cross-referenced using Wikipedia.

The benefits of the open model are numerous. Proponents hasten to point out how quickly knowledge can be updated and how crowdsourcing expands the potential pool of subject matter enthusiasts. At the same time, since the popularity of a topic is dictated by how many authors contribute to it, the length and depth (and potentially quality) of a given article is often directly proportionate to its popularity. This leaves less popular topics in a sort of black hole of obscurity where poor quality information reigns and novice authors go unchastised.

In fact, the Wikipedia page for “digital transformation” is the perfect example of this sort of balderdash. The first line of the wiki says,

Digital Transformation (DT or DX) is the use of new, fast and frequently changing digital technology to solve problems.

Except that’s not really the case. Although technology is certainly a key ingredient in digital transformation, changing the business model and the way the organization interacts with consumers is at the core of digital transformation. Technology enables fundamentally new ways to do this, but technology alone is not sufficient.

Many agree that the quality of Wikipedia articles is not sufficiently high for academics but “good enough” considering that it is free and an open model. Some proponents even argue that the “open” nature of Wikipedia reduces bias and thus improves quality through each revision by new authors. I doubt this is the case across the board. Just try to convince the moderator of a particular page to remove erroneous content, and you’ll see what I mean. And even if bias is reduced, there is little that prevents a swinging pendulum of one author’s erroneous post to another that is no better.

Hey Siri and Hello Alexa

In some ways, Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa are the digital logical extension of Wikipedia, the Internet, and knowledge as a whole. In a sense, these digital assistants are more than a channel or method for accessing information. One must ask whether Siri and Alexa create information given the fact that essentially knowledge searching is being crowdsourced by these tools.

Encyclopaedia Britannica agrees. In fact, they do not see the free content of Wikipedia as direct competition. They recognize that they will never get as many “hits” as Wikipedia. They also understand that they will never be able to update knowledge as quickly as Wikipedia. At the same time, they believe there is value in retaining subject matter experts to vet knowledge, organize it, and write about it in an accessible way. They have tweaked their approach to curation, though. Now, about 33% of their content is contributed through an open model, but it is still ultimately vetted by experts and editors.

The Perpetual Evolution of the “Dictionary of Digital Business”

It is an understatement to say that the Dictionary of Digital Business is not comprehensive. It is more like a starting point or “stake” in the ground. Your thoughts, comments, and suggestions are important to make this a “living” and evolving document. Think of this as a dictionary of perpetual evolution. Just as digital transformation constantly changes, this document will evolve with it. As items are added or described in greater depth, it has the potential to evolve into an Encyclopedia of Digital Business. Please share this information and contribute to it.

It seems fitting to end with a quote from Diderot:

What gratitude the next generation following such troubled times would feel for the man who had . . . taken measures against their ravages by protecting the knowledge of centuries past.